Abney Park: a hidden treasure in north London

A serotinal morning announces itself by blending

extant estival greens with emerging autumnal reds. Perfect start for a

Covid-delayed tour of London’s Magnificent Seven. These are Victorian-era

cemeteries that were created to ease pressure on parish burial grounds.

It’s logical that as a north London resident I kick

off at Abney Park, a graveyard opened in 1840, in nowadays trendy Stoke

Newington. I don’t spend much time inside, though. I’m so used to these

grounds, having found them by chance many years ago, on one of my many cycling

jaunts. During the first lockdown in 2020 Abney was one of the two places,

along with nearby Clissold Park, my girlfriend and I frequented.

Today I come across early-rising runners, friendly

dog-walking strangers and school-age children following anxious-looking

parents. Abney’s location serves as a quiet short cut between Stoke Newington

High Street’s hustle-bustle and Stoke Newington Church Street’s café life with

the added bonus of chancing upon famous graves.

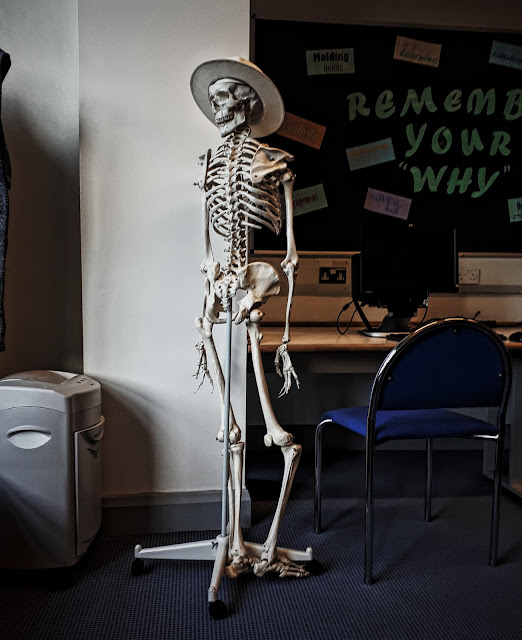

Like those belonging to the non-conformists buried

here. These were rebels who defied the ways of the Church of England and

refused to align with a particular Christian denomination. The chapel (derelict

and rundown, though it is) was designed in a manner that showed no bias towards

a single Christian sect.

In addition, if like me, you are into the music of

the late singer Amy Winehouse, you’ll be interested to know that her video “Back

to Black” was partly shot here.

With the sun beginning to beat down on the pavement

and my stomach rumbling, I hop back on my bicycle and head off for my second

destination: Tower Hamlets Cemetery Park.

No matter which route I choose, everywhere is

bumper-to-bumper. The start of the academic year, road closures and the

proliferation of LTNs (low traffic neighbourhoods, a polarising issue if ever I

saw one) means that from Amhurst Road and all the way down Mare Street to Roman

Road, I have to zigzag my way around buses, lorries and cars.

Some years ago I came up with a moniker for this

area: the Hipster Republic of North, North-eastern and Eastern London. Its

borders have changed slightly (gentrification works in mysterious ways), but

the core of it remains the same. It starts in N16 Stamford Hill and continues

through Stokey, Dalston, Hackney, Hoxton, Homerton and Shoreditch. From £5

bowls of cereal to ironic beards, from zany and thought-provoking graffiti to

checked shirts, this is the new, creative (and some might say, overpriced) London.

One of the tell-tale signs that lets you know you

have arrived in Hipster Land is the frames you see either on the road or

parked. I’ve been dipping in and out of Laurent Belando’s excellent book, Urban

Cycling, so I’m able to recognise some of the specimens. The bicycle par

excellence in these parts is the fixie, or its close relative, the single

speed two-wheeler. Understandable when you notice how flat most of east London

is.

But it’s not just the road surface that contributes

to the ubiquitousness of these machines. Both fixie and single speeds are

fashion statements. Their cultish and aesthetic appeal is all part of the

phenomenon I’ve come to describe as “the individualisation of cycling” (some

people would call it “fetishisation”). A bicycle is not just a bicycle. A bicycle

is an extension of a rider’s individuality.

Furthermore, there’re also the professions.

Fixie/single speed owners tend to belong to that turn-of-the-century cabal that

spread slowly through previous no-go areas in east London (I still remember

when someone told me Mile End was known as “Knife End”) bringing rents and

house prices up. They are the artistic directors, marketing managers, graphic

artists, web designers, performers, project managers, communications and media

managers. Of course, their bikes have to say something about them in the same

way the brands they create say something about their company.

Following hot on the (w)heels of the fixie and

single speed come the road bike, porter bike and vintage two-wheeler. Today I spot

an equal number of these frames on the road. From just past Hackney Empire to

Old Ford Road, off Cambridge Heath Road, they seem to be everywhere.

Out of the three, it’s both the porter and vintage

bikes I’ve got a soft spot for. Road bikes, or “racing bikes” leave me cold.

Perhaps, it’s their aggressive look, too much Tour de France, incongruous on

these narrow streets.

The porter and vintage bikes, on the other hand,

invite effortless elegance and style. Today I see a lot of what was formerly

known as girls’/women’s bicycles and have been thankfully re-baptised as “step-thru

bikes”. Just a clever way of convincing gents that they don’t have to swing their

legs over their seats the whole time to prove they’ve got a pair.

Rolled-up yoga mats poke out of baskets

sitting at the front of porter bicycles. In others, pooches sit comfortably, a

gentle breeze ruffling their hair. In open defiance to speed or terrain, porter

and vintage bikes are the non-conformists of our age. Perhaps a place at Abney

is already waiting for them when they reach the end of their cycle.