all ye who enter here.'

Inferno

Dante Alighieri

Prisoner 174517 never forgave the Nazis. Let me repeat that. Häftling Nummer Eins-Sieben-Vier-Fünf-Eins-Sieben never forgave the Nazis. True, by his own admission his personal temperament was not inclined to hatred. Even less did he accept ‘hatred as directed collectively at an ethnic group, for example, all the Germans’. Nonetheless, he never forgave 'any of the culprits, nor was he willing to forgive a single one of them, unless he had shown that he had become conscious of the crimes and errors of Italian and foreign Fascism and was determined to condemn them, uproot them, from his conscience and from that of others’. Only then he was ‘prepared to follow the Jewish and Christian precept of forgiving one’s enemy, because an enemy who sees the error of his way ceases to be an enemy’.

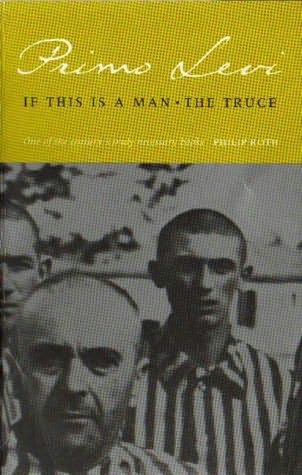

Primo Michele Levi (1919 – 1987), prisoner number one-seven-four-five-one-seven, was a Jewish-Italian chemist from Turin who in 1943 helped form a partisan band, which he and his comrades hoped, would eventually be affiliated with the Resistance movement ‘Justice and Liberty’. Some time later he was captured by the Fascist militia and sent to a detention camp at Fossoli. His final destination, though, was Auschwitz.

‘If This is a Man’ details Primo’s stay at Monowitz, one of the work-camps, (Arbeitslager) in Auschwitz. For eighteen months until the end of the war in 1945 he laboured behind electric barbed wire. I write ‘laboured’, but please understand that the correct phrase would be ‘slaved away’, for this was employment under duress in sub-human conditions. Forced to jettison everything he held dear, this was a man who became hollow like many others and who was reduced to suffering and grief. Deprived of his habits, his clothes and everything he possessed, his captors achieved the unachievable: divest him of his humanity.

For anyone who still thinks that the Endlösung (the Final Solution) was merely the work of a megalomaniac, deluded by his own political rhetoric, ‘If This is a Man’ is obligatory reading. The systematic degradation and humiliation of millions of prisoners in the work-camps was part of the grand master plan of advancing Germany both economically and politically in Europe first and in the rest of the world afterwards. The shaved heads, striped clothing and wooden clogs were just elements in Hitler’s geopolitical game circa 1938.

And how much was the West to blame for Hitler’s success in this political bingo? Historians disagree about the degree of guilt apportioned to nations like Britain, France and the former Soviet Union, what they don’t disagree upon anymore is that these countries all shared a huge chunk of responsibility for the Führer’s achievement in seizing Austria first and Czechoslovakia afterwards. It is a known fact nowadays that the two aforementioned nations were almost sacrificed to Nazi Germany in exchange for a pact of no aggression. That the German leader violated this agreement should not have come as a surprise especially after the inflamed and rabid political rhetoric of his speeches. It was precisely these tirades that led to the pogrom of 9th and 10th November in 1938 when an orgy of violence led to the rounding up of 30,000 male Jews who were later sent to concentration camps.

‘If This is a Man’ therefore gives us a powerful insight into the Nazi machinery once it got hold of power and stuck its poisonous forked tongue out. Total obedience in the work-camps was compulsory. German was the only language spoken and because many prisoners did not have a good command of the lexicon, not even basic knowledge, they were regularly submitted to beatings and corporal punishments. Questions were never asked. Primo Levi learnt the value of food very quickly: the bottom of bowls had to be scraped, as well as held under the chin when eating bread so as not lose any crumbs. Thefts happened very frequently therefore one’s possessions (possessions, what an odd word when what we actually refer to is one’s spoon or piece of wire to tie up one’s shoes!) were never left out of sight, even when taking a shower.

The second book, ‘The Truce’ deals with Primo Levi’s tortuous journey back home. Whereas ‘If This is a Man’ is about the gradual dehumanisation of the human being inside all of us (bar a few examples here and there), its follow-up is all about endurance and resilience, two human virtues that are often overlooked in our search for more practical acts of heroism. Of the 125 people Primo entered Monowitz with in 1943 only three went back home. One of them was the author.

Levi’s odyssey back to Italy was perilous as it was long. Due to bureaucratic and amateurish errors by the liberating Russian forces, his itinerary took him east first and then west, encompassing regions as varied as Katowice in Poland and Brasov in Romania. Throughout this trip the constant danger of Nazi escapees loomed large and it was only when the five-hundred-yard-long train, taking him and the other ex-prisoners home, departed from Starye Dorogi in the former USSR to Iasi in Romania that their patience was rewarded.

Back home in Turin, the book’s final pages reverberate like a trumpet announcing an evening cry or a parent calming their child down after they have had a terrible nightmare. The difference is that this nightmare was real.

One of the questions Levi was frequently asked was how much the Germans knew about what happened in the concentration camps. His analysis in the book was thorough and honest. In it he addressed the reality of totalitarian regimes (criticising the Soviet regime, too) and their attempts to curtail freedom of speech as well as the imposition of only one Truth. Although this might seem like a mitigating factor that worked to the Teutons’ advantage Levi was quick to point out that ‘it was not possible to hide the existence of the enormous camp apparatus from the German people. What’s more, it was not (from the Nazi point of view) even desirable. Creating and maintaining an atmosphere of undefined terror in the country was part of the aims of Nazism’.

Apparently Primo Levi was unable to shake off this atmosphere of terror and rumours abound that his accidental death in 1987 when he fell from the interior landing of his third –floor flat was really suicide. Whether it was his own volition that led him to take his own life or it was a fortuitous event, ‘If This is a Man/The Truce’ remains one of the most powerful testimonies of the horrors of Nazism and the consequences of authoritarian regimes.

Copyright 2008

Nice one. I think the opening was fantastically written...

ReplyDeleteThanks, ony. It was the least I could for such a great writer.

ReplyDeleteGreetings from London.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteVi que estabas leyendo el libro de Primo Levi hace un tiempo. Yo siempre crei en la teoria del suicidio de P.Levi. Conocio, como dices tu, la deshumaniazcion del ser humano y despues de eso no todos pueden recuperarse y ver la vida como antes. A Levi lo trataron de exterminar pero el solo eligio cuando irse.

ReplyDeleteEste autor y Elie Wiesel son los dos escritores que personalmente mas me han impresionado en sus relatos sobre los campos de concentracion y el efecto psicologico en los sobrevivientes.

En cuanto a si lel pueblo aleman sabia de la existencia de los campos creo que cuando uno no quiere ver es muy facil de andar con parches como los caballos. Los paises de la alianza si sabian de la existencia y eligieron de no bombardear las vias de trenes que llevaban a los campos por diferentes razones. Quisiera creer que la comunidad internacional reaccionaria diferente hoy en dia...

gracias (oye, te molesta que siempre te escriba en espaniol)

saludos,

No me molesta para nada, lena! Por supuesto que puedes escribir en la lengua que te venga en gana :-)

ReplyDeleteEstoy muy de acuerdo contigo en lo del suicidio,pero como se que hay gente que no esta de acuerdo, lo dejé entre comillas, como aquel quien dice.

Estoy completamente contigo en que cuando una persona sufre lo que sufrio este hombre, su mundo interno se desbarata y le cuesta an-os poder armarlo de nuevo. Y solamente tenemos una vida.

En cuanto a los alemanes, no hay peor ciego que el que no quiere ver. Por mucha propaganda nazi, fue ventajoso que para la mayoria de ellos que fueran los judios los conejillos de India porque asi no tenian que buscar una raza nueva. Los semitas han sufrido persecucion tras persecucion durante siglos, asi que cuando llego la hora de coger a alguien pa'l trajin, ya existia una base. Y yo pienso que desde el parvulo de dos an-os hasta los oficiales mas altos de la GESTAPO vieron a los judios como el chivo expiatorio apropiado.

Gracias por pasar.

Saludos desde Londres.